The Majestic North American Bison

The worst animal genocide in history and the greatest recovery from the brink of extinction

The American Bison, also known as the American Buffalo (Bison bison), is the Official Mammal of the United States. In addition to the American Bison, officially known as the Plains Bison, that inhabited much of the United States, the Wood bison (Bison bison athabascae), a subspecies of the American Bison, inhabited the boreal forest regions of Alaska, Yukon, western Northwest Territories, northeastern British Columbia, northern Alberta, and northwestern Saskatchewan.

The American Bison is the largest mammal in North America with weights ranging between 701 to 2,205 pounds (318 to 1,000 kg). The heaviest wild bull ever recorded weighed 2,800 pounds (1,270 kg) and, in captivity, the largest bison weighed 3,801 pounds (1,724 kg). These weights have never been confirmed and must thus be considered rumors. Most femailes will weight around 1,000 pounds and bulls generally 1600-1800, rarely over 2,000. They can stand at 6 feet to the hump. Despite their massive size, they are incredibly agile able to run at speeds up to 40 mph and jump 6 feet high from a standing position.

It is estimated that as many as 60 million American bison roamed the grasslands and plains of North America during the 19th century.

The North American Plains Bison has always been an integral part of early American life. The bison was not only a spiritual animal for the Native American people, particularly the Plains Indians, but Native Americans also depended upon these animals for their livelihood. Every part of the animal was often used: the hides constructed shields, saddles, and moccasins; bison hair made sturdy ropes and stuffing for pillows, and warmth for robes. The brain was even used for the preparation of hides, which was then used for the construction of teepees. The stomach lining made great cooking vessels and the contents were used for medicinal purposes.

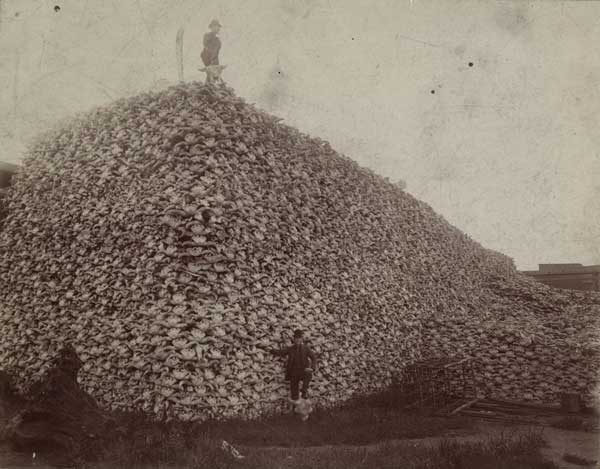

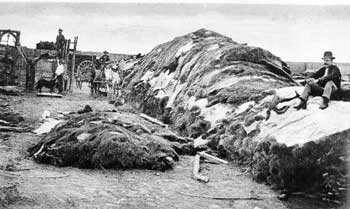

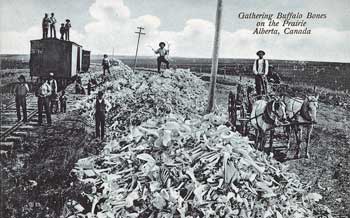

European explorers in North America saw the riches possible from bison fur and bison fur trading became a major industry with a fair number of trading posts appearing in the Great Plains. Buffalo hides were one of the major trade items from the plains brining between $1 and $3.50 each. Bison were hunted on foot, on horseback, and from trains for their tongues, hides, bones and little else. The tongue and the hump were (and still are) considered a delicacy. Hides were prepared and shipped to the east and Europe for processing into leather. The remaining carcasses were, for the most part, left to rot. When nothing but bones remained, they were gathered and shipped via rail to eastern destinations for processing into industrial carbon and fertilizer. Hearing of the amazing buffalo herds, wealthy hunters wanting to hunt the animals for themselves flocked to the Plains. Some hunters would shoot from the train as it passed the herds. This shooting did not supply any meat – it was just for sport.

But the fur trade and other commodities from the Bison is only a small part of the story. The American government encouraged elimination of the Plains Indians' primary food source, the bison. The idea was to kill off the Buffalo to starve the Indians, force them into relatively small areas, or north into Canada – make their food source either scarce or non-existent. The results would be starvation and high infant mortality amongst the Indian populations that would pave the way west for European settlement and the start of the western beef industry. Columbus Delano, the Secretary of the Department of the Interior said in the early 1870's, "Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone. "The rapid disappearance of game from the former hunting-grounds must operate largely in favor of our efforts to confine the Indians to smaller areas, and compel them to abandon their nomadic customs."

In the 1860's, the railroad needed fresh meat every day to feed the 1,200 railroad workers and the vast buffalo herds supplied the meat. The infamous Buffalo Bill once bragged that he killed 4,200 bison in seventeen months to feed rail laborers. Once the railways were built, large bison herds would sometimes cause lengthy train delays as the large herds crossed the tracks causing the rail companies to further promote the killing of the herds. When the monthly income average about $1,000, buffalo hunters were being paid $80.00 per day. The railways made it easy to devastate herd conditions and the railroad split the large bison herd into the southern and the northern herds. In just 40 years, from 1830 to1874, the southern herd was wiped out.

In addition to the fur trade and paid hunters from the government and railways, European settlers and the beef industry caused the introduction of bovine diseases from domestic cattle, further devastating the bison herds. By the early 1880s there were only a few free ranging bison left.

After the great slaughter of the American bison during the 1800s, the number of bison remaining alive in all of North America declined to as low as 541, with as few as 300 in the United States. During that period, a handful of ranchers gathered remnants of the existing herds to save the species from extinction. Had it not been for a few private individuals working with tribes, states and the Interior Department, the bison would be extinct today.

The genocide of the American Bison stopped and their recovery started in 1905 when William T. Hornaday, director of the New York Zoological Park (now the Bronx Zoo), created the American Bison Society and a breeding program in 1905, and became its president. Theodore Roosevelt helped protect the remaining buffalo and accepted the position as the society's honorary president. George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream magazine, attempted to save the herd of buffalo in Yellowstone National Park. Other than city zoos, along with a few private herds of ranchers, Yellowstone Park became the only refuge for the last remaining specimens in the United States, and there were only 23 bison left!

On October 11, 1907, the first 15 bison to leave the New York Zoological Society breeding program boarded a train to cross the country to Oklahoma to bring Bison to the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge. "The Buffalo Train Ride", a book by Desiree Morrison Webber (ISBN: 1571682759) describes that journey. In 1913, the American Bison Society donated 14 bison to Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota to restore a free-ranging bison herd.

Today, the National Bison Association puts the American Bison population at 400,000 animals with the goal of reaching 1 million within the next few years.

The United States Department of the Interior has been the primary national conservation steward of the American Bison herds on public lands and manages 17 bison herds -- or approximately 10,000 bison -- in 12 states, including Alaska. Yellowstone National Park is the only place in the U.S. where bison have continuously lived since prehistoric times. Although the original 23 remaining bison in Yellowstone were supplemented with approximately 25 bison from private Montana and Texas herds, Yellowstone's bison are the only pure descendants of early bison that roamed our country's grasslands. As of August 2016, Yellowstone's bison population was estimated at 5,500 -- making it the largest bison population on public lands.

Original range of the North American Bison.

Original range of the North American Bison.

| Date | Number of Bison |

|---|---|

| < 1800 | 60 million |

| 1830 | 40 million |

| 1840 | 35,650,000 |

| 1870 | 5,500,000 |

| 1880 | 395,000 |

| 1889 | 541 |

| 1900 | 300 |

| 1944-47 | 5,000 |

| 2016 | 400,000 |

| Dates | Bison Population | Pressures on Bison | Legislation | Recovery Efforts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 798,000 BC | Bison cross the land bridge | |||

| 1500's | 60 million | |||

| 1690 | Henry Kelsey, reported that the Cree Indians called these noble animals Thatanka, which the English of his day called "buffillo." Although actually bison, since first sighted by Europeans, the name buffalo has stuck in common parlance. | |||

| 1700's - 1800's | 30-60 million; | As Euro-Americans settled the country, moving westward from the east coast, they brought changes to native habitat through plowing and farming. Introduced cattle diseases and grazing competition with feral horses also impacted bison prior to direct impact by Euro-Americans. | ||

| 1802 | Bison gone from Ohio, pushed out by pioneers and settlers. | |||

| 1804-06 | Lewis and Clark expedition travels the upper Missouri River. | |||

| 1816 | The Evening Post lists buffalo skins for sale and the Pittsburgh Gazette lists 500 Buffalo Robes for sale by Bosler & Co. | |||

| 1819 | Bosler & Co lists 70 bales of Buffali robes for sale and George Astor lists 1000 Buffalo ropes for sale. | |||

| 1820 | Bison extinct east of the Mississippi River. Native Americans tribes, forced off land in the east, bring horses and guns to the Great Plains and increased pressure on bison. | |||

| 1820-1880 | Buffalo robe market blossoms with trade routes and posts throughout the Northern Plains. Large numbers of buffalo robes being offered for sale. | |||

| 1830 | 40 million | Mass destruction of the once great herds of bison began. | ||

| 1832 | The artist George Catlin says, "The buffalo's doom is sealed." | |||

| 1840's | 35 million | West of the Rocky Mountains, bison (never in large numbers) disappeared. Native Americans market hunters concentrated on cow bison, because of their prime hides for trading. | ||

| 1844 | This may have been the peak year for the Hudson Bay Company as 75,000 bison robes were traded to posts in Canada. | |||

| 1859 | General Randolph B. Marcy journeyed from Fort Randall on the lower Missouri to Fort Laramie without seeing a single buffalo. This convinced him that the animals were "rapidly disappearing, and a few years will, at the present rate of destruction, be sufficient to exterminate the species." | |||

| 1860's | Railroads built across the Great Plains during this period divided the bison into two main herds - the southern and the northern. Many bison were killed to feed the railway crews and Army posts. During this time, Buffalo Bill Cody gains fame. Cattle disease raging among the buffalo on the Northwester prairies is reported in newspapers. | In 1864, the Idaho State Legislature passed the first law to protect the bison - after they were gone from the state. | In 1866, Charles Goodnight captured a few free ranging bison calves and began a captive herd on his Elk Creek Ranch, Throckmorton County, Texas. The bison were sold shortly after, unbeknownst of Mr. Goodnight whiler he aws on a cattle drive. | |

| 1870 | 5.5 million | An estimated two million bison were killed this year on the southern plains. Germany had developed a process to tan bison hides into fine leather. Homesteaders collected bones from carcasses left by hunters. Bison bones were used in refining sugar, and in making fertilizer and fine bone china. Bison bones brought from $2.50 to $15.00 a ton. Based on an average price of $8 per ton they brought 2.5 million dollars into Kansas alone between 1868 and 1881. Assuming that about 100 skeletons were required to make one ton of bones, this represented the remains of more than 31 million bison. | It became obvious in the 1870's that owning bison was profitable. More and more people were capturing free ranging bison to establish private herds. | |

| 1871 | This year marked the beginning of the end of the southern herd. The greatest slaughter took place along the railroads. One firm in St. Louis traded 250,000 hides this year. Demand for bison skins escalated as a Pennsylvania tannery began commercially tanning bison hides. With this newly discovered tanning process, bison were now hunted year round. | Territorial delegate R.C. McCormick of Arizona introduced a bill that made it illegal for any person to kill a buffalo on public lands in the United States, except for food or preserving the robe. The bill indicated that the fine be $100 for each buffalo killed. Mysteriously, this document disappeared. Wyoming passed a law prohibiting the waste of bison meat. Since such laws were not enforced, they did little to protect the bison. | ||

| 1872 | During this year and the next two, an average of 5,000 bison were killed each day, every day of the year, as ten thousand hunters poured onto the plains. One railroad shipped over a million pounds of bison bones. Bison hunting became a popular sport among the wealthy. | The Kansas legislature passed a law prohibiting the wasting of bison meat, but the Governor vetoed it. Colorado passed a law prohibiting the wasting of bison meat; it was not enforced. The legislation creating Yellowstone National Park provided against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found in said park. Staffing and funding were not provided to enforce this law. | ||

| 1873 | On the southern plains, slaughter reached its peak. One railroad shipped nearly three million pounds of bones. Hides sold for $1.25 each, tongues brought 25 cents a piece - most of the bison was left to rot. A railway engineer said it was possible to walk 100 miles along the Santa Fe railroad right-of-way by stepping from one bison carcass to another. | Columbus Delano, Secretary of the Interior, under President Grant, wrote in his 1873 report, "I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in the effect upon the Indians. I would regard it rather as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their own labors." | In 1872 or 1873 with the aid of his wife Sabine, Walking Coyote, a Pend Oreille Indian, acquired some bison calves, bringing them into the Flathead Valley with the intent of starting a bison herd. In Canada, west of Winnipeg, James McKay acquired five bison and established a small herd. | |

| 1874 | This year marked the seeming end of the great southern herd. Auctions in Fort Worth, Texas were moving 200,000 hides every day or two. One railroad shipped nearly 7 million pounds of buffalo bones. | Congress advanced their efforts to save the bison. Both the House and Senate passed a bill that protected female bison and did away with wanton destruction. However, President Grant refused to sign the bill. | Around this time, William and Charles Alloway of Manitoba, Canada, with the aid of a milk cow, captured three bison calves to start their own herd. | |

| 1875 | Few bison remained in Texas when the state legislature moved to protect the bison. However, General Phil Sheridan appeared before the assembly and suggested that every hunter be given a medal with a dead buffalo on one side and a discouraged Indian on the other. He added that once the animals were exterminated, the Indians would be controlled and civilization could advance. | |||

| 1876 | The estimated three to four million bison of the southern plains were now dead. The Northern Pacific Railroad, anxious to advance, ignored tribal treaties and sent in a survey party. Native Americans killed some of the men, and General George Custer was sent to investigate, making history with the Battle at Little Big Horn. | |||

| 1877 | A few remaining free roaming bison were discovered in Texas and were killed. | A law was passed in Canada that forbade the use of pounds (corrals), wanton destruction, killing of buffalo under 2 years of age, and the killing of cows during a closed season. | Lt. Col. Samuel Bedson of Stoney Mountain, Manitoba (Canada) purchased bison from the Alloway herd, the McKay herd and from some Native Americans. | |

| 1878 | Bison in Canada were disappearing rapidly. | Canada repealed the 1877 law. | ||

| 1880 | 395,000 | Slaughter of the northern herd had begun. | New Mexico passed a law to protect the bison; unfortunately the bison were already gone from this state. | |

| 1881 | This years winter marked the largest slaughter of the northern herd. One county in Montana shipped 180,000 buffalo skins. Robes brought $2.50 to $4.00 each. | Around this time, the Glidden and the Dupree herds (of the Dakotas) were established. | ||

| 1882 | Over 10,000 bison were taken during one hunt of a few days length in Dakota Territory in September. The fate of the northern herd had been determined. Hunters thought that the bison had moved north to Canada, but they hadn't. They had simply been eliminated. | |||

| 1883 | By mid-year nearly all the bison in the United States were gone. | The Dakota Territorial Legislature enacted a law to protect bison; it was not enforced. | In Oklahoma, the McCoy brothers and J.W. Summers caught a pair of bison calves, 2 of very few left on the southern plains. | |

| 1884 | There were around 325 wild bison left in the United States - including 25 in Yellowstone. | Congress gives the Army the task of enforcing laws in Yellowstone National Park in an effort to protect the final few wild bison from poachers. | Charles Goodnight re-established his herd. Michel Pablo and Charles Allard of Montana purchased 13 bison from Walking Coyote for $2000 in gold. | |

| 1885 | C.J. Jones purchased a few bison from Charles Goodnight, along with capturing 13 bison from southern Texas, starting his own private herd. | |||

| 1886 | The Smithsonian Institute sent an expedition out to obtain bison specimens for the National Museum. After a lengthy search, some were found near the LU Bar Ranch in Montana. Twenty-five were collected for mounting and scientific study. (The original mounted specimens were brought to the Fort Benton (MT) Museum of the Upper Missouri in the mid-1990's, close to where the original bison were taken.) | |||

| 1887 | The American Museum of Natural History (New York), wishing to obtain their own bison specimens for an exhibit, mounted an exhibition to Montana. They found no bison. One of the last lots of bison robes sold in Texas for $10 per robe. | |||

| 1888 | Austin Corbin established a herd of bison on New Hampshire's Blue Mountain Game Preserve. | |||

| 1889 | 541 (US) (William Hornaday estimated total bison population to be just over 1000 animals - 85 free ranging, 200 in the federal herd (Yellowstone NP), 550 at Great Slave Lake (Canada) and 256 in zoos and private herds.) | Last commercial shipments of hides anywhere in United States. | ||

| 1896 | The Pablo/Allard herd in the Flathead Valley totaled about 300. Allard died, and his widow sold her portion to Charles Conrad of Kalispell, MT. | |||

| 1900 | 300 (US) | |||

| 1902 | There were 700 bison in private herds (US and Canada). The Yellowstone herd was estimated at 23 animals. | |||

| 1905 | Government bison herds held about 100 animals (Yellowstone NP and the National Zoological Park in Washington, DC). | The American Bison Society founded by private citizens to protect and restore bison. Ernest Harold Baynes, founder; William T. Hornaday, president; Theodore Roosevelt, honorary president. Hornaday (director of NY Zoological Park) gifted 12 of their bison to Wichita National Forest Preserve. This became the first gift of bison to establish/increase government herds. | ||

| 1906 to 1912 | Pablo sold his bison herd to Canada, after Congress turned down funding for purchase for the United States. After 7 years of rounding up, a total of 695 animals were shipped to Canada. Pablo received $170,000. The National Bison Society donated 6 bison to the Fort Niobrara Game Preserve. | |||

| 1908 | National Bison Range established for a permanent range for the herd of bison to be presented by the American Bison Society. | |||

| 1909 | Thirty-four bison purchased from the Conrad herd (Kalispell, MT) by the American Bison Society, donated and release on National Bison Range. | |||

| 1910 | The American Bison Society Census estimated 2,108 bison in North American (1,076 in Canada and 1,032 in the U.S.). Bison in public herds in the U.S. totaled 151. | |||

| 1913 | Wind Cave National Park (SD) received 14 bison from the New York Zoological Society. | |||

| 1919 | Estimated population of North American bison at 12,521 (US and Canada). | |||

| 1924 | The National Bison Range donates 218 bison from a herd total of 675 to other public herds. This is the first of many donations and sales of live bison. | |||

| 1935 | Because of the secure populations of bison in public herds, the American Bison Society votes itself out of existence. | |||

| 1940's | 5,000 (US) | |||

| 1990's | An estimated 20,000-25,000 bison were in public herds in North America. At least 250,000 bison in private herds by end of decade. |

Private bison herds on the rise. Many bison raised for eventual slaughter - selling point of bison meat is it leanness and low levels of cholesterol. Many Native American Tribes reintroducing bison to their lands through the effort of the InterTribal Bison Cooperative and donations from federal herds.

In 1995 the American Bison Association (formed in 1975) and the National Buffalo Association (chartered in 1966) merged to become the National Bison Association (NBA). The NBA has more than 1,100 members in all 50 states and 10 foreign countries with a vision bound by the heritage of the American Bison. Their mission is to bring together stakeholders to celebrate the heritage of American bison, to educate, and to create a sustainable future for the industry. |

||

| 2016 | 400,000 | The National Bison Association and the United States Department of Agriculture puts the current Bison population at 400,000 animals. The goal of the NBA is to hit the 1 million mark in the next few years. | ||

| Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service; All about Bison: Yellowstone;Bison in History | ||||